The Rise (or Fall) of A-Pop, Pt. 5

Part 5: The world after blockbuster American pop—impersonators, mirages, and post-pop impressionism

All installments Part 1 || Part 2 || Part 3 || Part 4 || Part 5 || Part 6

The other day I asked my kids what music sounds old to them. I noticed that they had been listening to a lot of music from the early ‘10s, and I was thinking about how at a recent school dance so many floor-fillers were from before most of the kids were born (the oldest kid there was born in 2014). I couldn’t imagine any songs from 1979-1982 playing at my grade school functions in the ‘90s, except maybe “Y.M.C.A.” by the Village People, which is timeless, but which I also assumed was older than dirt.

When I was a kid, I listened to lots of old music that didn’t sound so “old” to me. Some of it was really old: Dr. Demento tapes with music from the swing era or earlier, or the “golden oldies” radio station that was the only one both parents agreed on and rarely played any music past 1964. I recognized the music as old, but it didn’t always feel old in the uncanny way other music did—in fact, I often had no time schema for it at all, and this was thrilling to me.

But other music was coated in the unfashionable dust of recent history and seemed unapproachable. These were rarely “oldies,” per se; they were songs that had come out only a few years before I was born. The synth sounds of new wave were for the near-adults in my life. ‘70s dinosaur rock smelled like stale beer. Disco might as well have been in sepia, music for grandmothers at weddings. And it wasn’t just older music: even music that was only a few years old seemed to age horribly as I got older—by 1994, when I was in 5th grade, I would have thought it was mortifying to hear Vanilla Ice or Paula Abdul on the speakers, despite loving them a few years earlier. I had not only a sense of how old things were, but of how much older they felt as time went on, every year away from their release date another lifetime ago.1

My kids don’t seem as hung up on these distinctions. Whereas when I was their age, a span of five or ten years could put something at an unbridgeable remove, my kids’ favorite songs when they were very little (and came out before they were born) are not only still favorites, but they get regular airplay in schoolyards and at dances and in summer camps. I hear these songs everywhere, as though they’ve been preserved in amber—I heard “Call Me Maybe,” “Party in the USA,” and Katy Perry’s “Roar” many times this summer.

My kids’ sense of when any of these songs were released is sketchy. My oldest guessed that “Party in the USA” was from 1995, a few years after Whitney Houston’s “I Wanna Dance with Somebody (Who Loves Me)” (1991, he guessed), and that “Roar” by Katy Perry sounded even older than that, but then, catching himself, thought that logically it must have come out sometime much later. “Call Me Maybe” by Carly Rae Jepsen he put correctly at 2011. Then he second-guessed all of his other dates, and then shrugged it off, saying that this was a really fun game and we should do it again sometime (challenge accepted).

I was struck by how he described these songs in retrospect:

“None of those songs sound old to me—it doesn’t sound like parent music. It sounds like music from when I was younger.”

My kids also don’t really know when a lot of more modern American pop was released, either, because they don’t listen to much of it. They may have some familiarity with it, but it’s often through Kidz Bop versions in music class or times that radio-edited versions get played in public spaces. The blurry demographic reach of MTV and pop radio in the ‘90s has been ruthlessly sharpened and segmented, a somewhat paradoxical effect of the infinite access of the internet, which I guard more carefully than my conscientious parents ever guarded the remote control.2

By my reckoning, that gives my kids, who are by no means a representative sample but are unfortunately for these purposes the only subjects I have access to, reasonably strong knowledge of some of the biggest pop music from the mid-1980s to the early 2010’s (Michael Jackson and Madonna through Taylor Swift and Katy Perry), and extremely spotty knowledge of what came after, during their early childhoods.

This seems very unlike my own experiences growing up. I wasn’t obsessed with music as a kid, but I kept up with pop music with a kind of casual religiosity, like going to church out of a sense of begrudging obligation. I have strong associations between the pop songs of any year between about the ages of six and sixteen and what role these songs played in my life. My own kids just don’t seem to care very much in that way, and their listening reflects both a wider range of music, from different global regions and time periods, and also less interest in contemporary American pop.

But maybe it was my life that was unusual.

American pop had two related phases of global influence, and I was born in between and was shaped by the impact of both of them. The first is the postwar turn to globally dominant American pop forms—rock ‘n’ roll, soul, country—which loosely map on to American economic and (I think to a lesser but not irrelevant extent for music) military hegemony, and the accelerated development of these forms in the 1960s. The second is the rise of blockbuster pop in the mid-1980s, with music selling at an even bigger global scale, more or less in line with information and trade globalization. The second phase is predated by what I always heard as rock music fighting and struggling for relevance and the ascension of dance music through funk and disco (this is also the music that sounded old to me as a kid—the most exciting music from this period I didn’t hear until I was much older).

The first postwar phase of America taking a central, global music role is something I inherited through my parents and more or less took for granted as being the foundation of all subsequent pop forms. My dad played guitar in the late ‘50s for what he called the second-best rock ‘n’ roll band in Meadville, Pennsylvania, and my mom was as hippie as was required to dig the Mamas and the Papas. I absorbed the Beatles and Beach Boys from the radio and friends’ families. The Rolling Stones freaked me out a little.

The second phase of outsized American pop stars—starting around 1983, the year before I was born—defined the music of my childhood, and though some pop music became immediate and seemingly permanent standards (Michael Jackson, Madonna, Whitney Houston) much more of it came and went with ferocious speed and force. No sooner could I sketch MC Skat Kat from memory than Paula Abdul had vanished. Ace of Base were inescapable for a year, like a scout probe before the Swedish teenpop invasion, and then they were gone. Every year brought new superstar casualties: New Kids on the Block, MC Hammer, Billy Ray Cyrus, Boyz II Men, Hootie and the Blowfish, Coolio, Hanson—all of them burned brightly and then became a “had to be there” time capsule.

This constant churn is not something I recognize in the childhood of my parents, even though music history moved quickly for them. The genesis of rock ‘n’ roll and other postwar music would get mined and rerecorded and reimagined for the better part of a decade or more, and my parents’ canon was gifted to me more or less intact.3 Pop churn is also not something I recognize in my kids’ lives, where they constantly discover old music—a Michael Jackson phase here, a mid-’10s EDM phase there—that sounds exciting and new to them without ever worrying about pop songs racing toward them like Lucy and Ethel eating chocolates at the conveyer belt.

The blockbuster American pop era that I experienced was a bubble that burst sometime around 2010. The thing that popped it was a shift to new globalized forms of access that finally matched the promises of globalization—a phenomenon that had suggested bilateral relationships but for a long time mostly just served as a bigger and bigger engine for American and other western content to be delivered to the rest of the world, with only a few exceptions traveling the pipelines in the opposite direction.

The shift to streaming not only opened up listeners to many new avenues for hearing songs from other times and other places. It also eliminated many of the mechanisms through which American pop distributors could regulate and eventually cycle out artists and hits in the national charts. This shift effectively broke a monopoly on American pop blockbusters, a power used not only to create monsters but to rein them in, too.

You see this when you take a look at who succeeds, and for how long, on the Billboard Artist of the Year lists. I like the Artist of the Year charts because they aren’t entirely subjective, though they’re certainly (seemingly) massaged. They use chart data formulas to come up with their rankings, but they are also snapshots: they don’t require forms of sales accounting that conflate lifetime sales with contemporary impact. It is also clear that these charts, first developed in 1981 and sensitive to changes in Billboard’s accounting over time (e.g. Soundscan, YouTube, and streaming), undergo a shift in the 2010s to fewer artists staying on the charts longer.

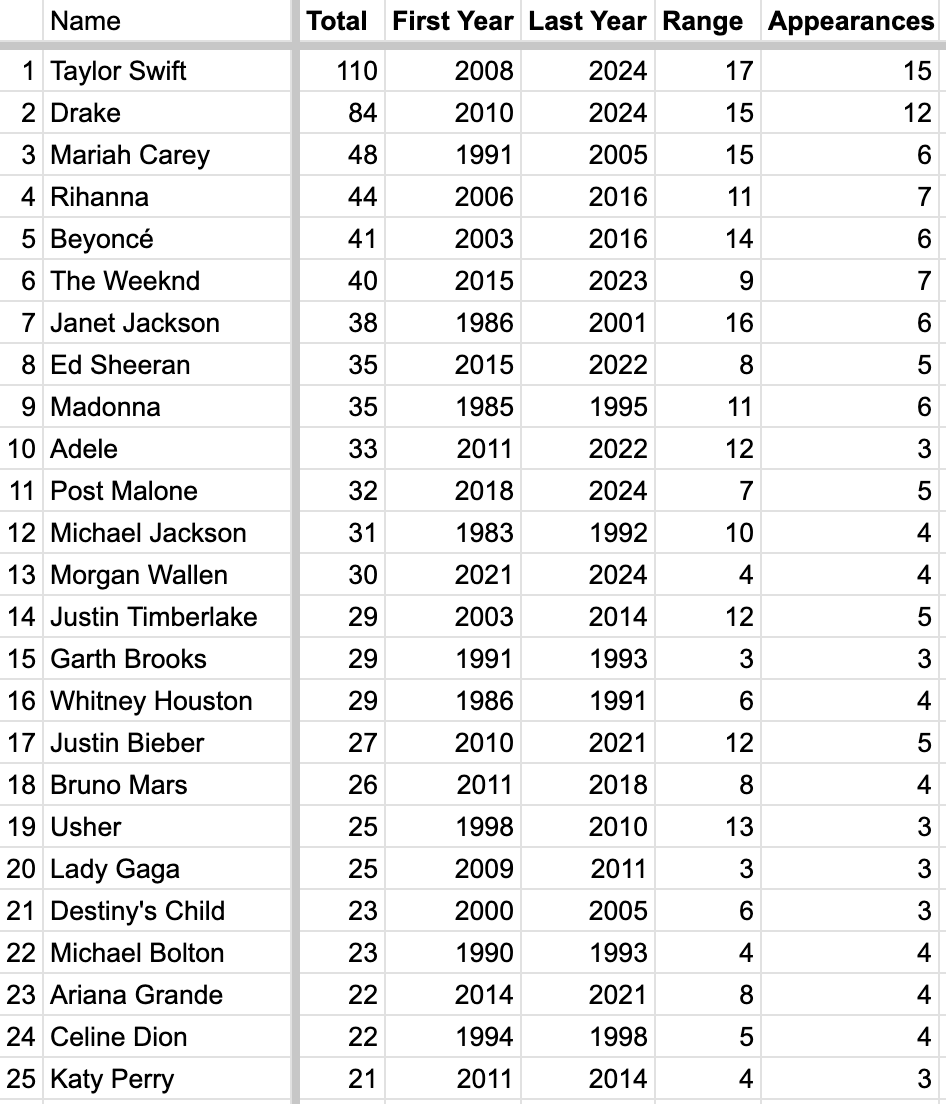

Here are the top 25 artists since 1981, ordered by their weighted scores for placements on the charts (10 points for a first place, 9 points for a second place, etc.). The chart also includes the time range of their appearances and their total number of appearances in the top ten.

Taylor Swift and Drake basically hijack these charts in the 2010s. They have double the weighted scores and number of placements than the next highest artists, and have to date been on the charts almost continuously for 15 or more years. They are the most extreme examples of a general trend: the 2010s has the lowest number of total artists listed (50, down from a high of 70 in the 1990s) and also the lowest number of artists who only appear in the top ten once (20, down from a high of 44 in the 1990s).

This methodology is unconventional to track pop history, but it gives you a sense of artists’ popularity in the context of their historical competition. Michael Jackson, the second-highest-scoring artist of the 1980s after Madonna by this metric, only has a lifetime score of 31 with 4 appearances. During his heyday, the competition was intense and there were powerful gatekeepers keeping his music out of rotation in years he didn’t release albums. His incandescent Thriller year was followed by Lionel Richie beating him in 1984 and then falling out of the top ten until the year after the release of Bad. (He was fourth in 1988, after George Michael, Def Leppard, and INXS.)

These lists also illustrate the erosion of artist gatekeeping in the transition to the streaming era. Big artists and songs in the 2010s stay around forever: radio has much less power to shape how long artists stay on the charts, while streaming platforms record the very long tails of what in previous decades would be unthinkably long album and single cycles.

If one impact of the end of old-school gatekeeping is the endless, stagnant reigns of megacelebrities, on the flip side we also get unpredictable popularity that is much more ambivalently global in nature. You can see this beginning at the start of the streaming era on charts of all-time views on YouTube, where “Despacito” and “Gangnam Style” are both still in the top 5. Many popular songs seem less obviously connected to an American pop lineage that runs from the mid ‘80s to the early ‘10s. The blockbuster pop phenomenon is still with us, but it is a global phenomenon no longer shaped by American gatekeepers, and it is not the unique province of American and western artists.

I think there was a corresponding shift to this emerging reality during the 2010s in American and broader western pop stardom: a pre-A-pop transition period. In the end of the American blockbuster era in the aughts, pop stars were still working to capture the promise of the original 1980s-derived pop landscape: they wanted to be the next Madonna, the next Michael, the next Whitney, the next Mariah. At the beginning of this new post-blockbuster era, though, the vast majority of would-be stars on the margins of success, and even a few very successful stars, adapted or tempered their ambitions in a few different ways.

What follows is my attempt to map out what happened after the end of the blockbuster era, but before the onset of what I call the A-pop era starting at the end of the 2010s. I’ve been conceptually organizing these paths into three categories: pop impersonators, pop mirages, and post-pop impressionists. Each category represents a different path away from the huge breakout successes of the end of the blockbuster pop era (those who debuted in or before 2010) and toward the more regionalized era of American pop that followed.

Pop impersonators

Pop impersonators do a sort of pantomime of tropes without really caring whether or not this signifies something new or interesting. This is a move that is common across pop history, especially as a sort of training stage—a big star starts out imitating someone else. Sometimes it works: that is, it might signify something new or interesting. But sometimes you just get a satisficing fulfillment of pop-star-like content (generic by design) in the hope of achieving pop star audiences, like an actor auditioning to be in a movie about a pop star.

There are at least two forms of impersonation, which are different and in some ways mutually exclusive, or at least in contradiction with one another. In one, an artist uses imitation as a kind of scaffolding to develop an original voice, literally or figuratively. In the other, imitation is a way for a star to be a savvy chameleon act that is flexible to trends and hard to pin down. This second type of impersonator’s strength is versatility more than a unique or even coherent personality. In the past, impersonators of this type were usually lesser pop celebrities—soundalikes and cash-ins. But the big impersonators of the 2010s like Bruno Mars and Ariana Grande were, if not original, unmatched, and often themselves used sounds and styles that self-consciously recalled older music.4

In the blockbuster era, pop impersonators usually played a minor role in a more robust ecosystem for pop stardom. Some of them wound up graduating to genuine pop stardom in the crucible of competition: they faked it till they made it. But in the 2010s, a few lucky artists just made it from the jump, taking advantage of a winnowing of the pop landscape to fewer huge names while bypassing the competitive field toiling underneath. The successful impersonators occupied a medium space between the previous blockbuster era’s stars and the new era’s nobodies.

I thought a lot about the interesting and sometimes productive tension between impersonation and originality tracking the millennial teenpop wave as a critic. Although teenpop simultaneously got airplay on adult contemporary radio and children’s radio, a specific variant of teenpop, largely originating from Disney, also often provided cleaner-cut alternatives to more risqué pop on mainstream radio. This was a field that intentionally cultivated lots of unabashed pop impersonators: cross-platforming actors or homegrown children’s music stars making music similar enough to mainstream pop to compete for relatively niche attention.

By about 2003, Disney had succeeded in building a closed-circuit ecosystem for itself with Hollywood Records to release its music and Radio Disney to broadcast it. At least one star of the Disney ecosystem, Miley Cyrus, was a success in the final wave of blockbuster pop (she first appeared in the Billboard Artist of the Year top ten in 2008 at #7, two slots below Taylor Swift’s first appearance). But most artists were in-house favorites or chart pop also-rans who struggled to break out of the Disney walled garden.

There hasn’t been much serious accounting for the role of Disney, Hollywood Records, and Radio Disney on the broader pop landscape in the aughts.5 What I want to emphasize is that the impersonator-pop of the Disney ecosystem was largely a sidestream to the actual chart-pop environment of the aughts.

It isn’t until about 2006 that you start to see a dissolution of the lines between Disney World and the Billboard charts. This process began with rule changes in 2005 that let a flood of digital downloads (notably High School Musical soundtrack songs) onto the “real” charts, and it ended with the first successful launches of Disney stars directly onto Billboard not as an explicit tie-in to a Disney show or movie, Demi Lovato and Selena Gomez, followed a few years later by Nickelodeon’s breakout star, Ariana Grande.

The opening of Disney’s walled garden became moot with the rise of Taylor Swift, who by 2009 had already eclipsed most of the Disney competition in the confessional teenpop space. But the template for child actors to impersonate their way to the top remained, often still through children’s television and a weakened distribution network, but with much less of a sense that there was any meaningful separation between child and adult audiences.

Pop mirages

A pop mirage is an artist posing as a pop star, usually temporarily, to lead a song. In some cases the singer remains practically anonymous; in others, a major or aspiring star gives their voice over to a hook in a way that feels like moonlighting from their “real” career. Often the star of the show is a DJ or producer, with the singer more of a collaborator or figurehead.

This is a lineage that I think is most legible through the role of lead singers in dance music and especially house. The dance music of the 2010s became a huge lane for charting pop music that nonetheless operated more like house music than it did like the singer-auteurist bent of other pop, where songwriting and production and performance combine in a synthesis represented by a marquee name.

But dance music is only one area in which new production norms were obvious. One thing that annoyed me about pop commentary through the aughts was the assumption of a faceless mass of producers and songwriters creating material indiscriminately and assigning it to singers basically at random. This absolutely happened, but my favorite music from this period usually came from creative teams working to build a coherent auteurist entity—from the Max Martin-style mecha pilot theory of pop machinery posited by Tom Ewing to the confessional pop songwriting teams I was drawn to a few years later.

In the ‘10s, writing norms fractured into shared credits for many more roles operating in a more piecemeal fashion, with songs sutured together and shopped to artists with much greater indifference: songs became mecha suits that were supposed to pilot themselves. This shift was exemplified by the growing importance of the topliner, a person whose primary role is to write a hook melody, as opposed to the production, lyrics, or other elements.6

This songwriting norm was a break from—or at least an acceleration or mutation of—the previous era. One reason toplining specifically became more widespread in both industry norms and cultural conversations is that the needs of ascendent dance-oriented genres in the early ‘10s for melodies were a bit different. Songs still needed high-impact choruses, but there was a certain agnosticism about what should produce the dynamics for the intended release: there might be a preceding verse, or there might just be an instrumental wash. In the case of late-period EDM-pop that I refer to as “bort-pop,” the lead-in to the release was a mess of scrambled syllables before an instrumental phrase in lieu of a sung chorus: post-topline mirage. But generally, EDM, dance-pop, and the big pop-rap choruses of the era required battering ram chorus melodies that followed the logic of the drop as the release.7

These songwriting and production norms made the role of the lead singer part of a more general texture of a song, almost daring a singer to signify personality (being able to do this was a rare skill). This could even be true of songs that featured big stars, who frequently granted their presence seemingly in name only to sing a hook. And it was also true for a new generation of dance-pop divas: Jess Glynne, Ellie Goulding, Becky Hill.

Pop mirages are often more like an instrument than a personality. But I think this period of mirage-pop did leave a legacy that eventually produced an interesting twist in the ‘20s, as less formulaic, faster, and stranger dance-pop trends became more popular. This newer music features auteurist mirages—not personalities reduced to instruments, but instruments elevated to personalities.

Post-pop impressionists

The thorniest category is what I call the post-pop impressionists. I mean “impressionism” in the art world sense, getting at pop obliquely using elements that only give you an impression of the thing holistically. The post-pop impressionists are very close to what I’ve called, in the third part of this series, the middlestream. But they have more of a feel of the old school of pop star—and they often make for more interesting pop personalities than the artists trying to recapture a faded former era of stardom (the impersonators) or those not really bothering with pop stardom at all (the mirages). Their only problem is that they usually aren’t very popular.

The successful ‘10s post-pop impressionists started their careers in spaces that weren’t fully accepting of them, carving out a much bigger audience from a general public without always having the strong backing of their intended scene. The basic audience-building move is very similar to what Taylor Swift did with the teenpop audience of the late aughts while starting in country music. In some ways you might think of Swift in this category—the biggest cult act of all time. But the audiences for these other stars never got close to the scale Taylor Swift achieved with her timing.

Lana Del Rey, Grimes, and Sky Ferreira all received early praise in indie spaces: Del Rey and Ferreira went through early major label development hell to ultimately court cooler audiences, while Grimes started on indie label 4AD. Charli XCX shifted from being a rave and club kid putting weird music on MySpace to chart pop, and, later, did something similar in the British hyperpop scene: a kind of underground translator for a larger pop audience. Charli XCX’s talent has been serving as a kind of cultural power adapter between sidestream and mainstream.

Lorde’s breakthrough with “Royals” in 2013 might be the biggest single event in giving post-pop impressionism a real shot at megastardom: it was one of the extremely rare songs that went to #1 on both the alternative rock charts and the Hot 100. Lorde is an interesting test case in how huge you can be—and in some ways remain—without being able to parlay this into sustaining pop stardom. In fact, Lorde’s most enduring impact on pop was probably being cannibalized by Taylor Swift and defining Swift’s music after 2014.8

Although the stardom of the post-pop impressionists is legible, it isn’t exactly starry. The end of the American blockbuster pop era put people who follow American pop closely in a bit of a wilderness: there is often a sort of special pleading among pop enthusiast critics to recast our understanding of pop stardom to a smaller scale, so that the conversation can be about pop stars while ignoring the “star” part, not dissimilar to indie rock’s relationship to rock history. It makes pop artists who have never gotten close to the sales or stature of the big unmovable names of the previous decade seem to be competing on their own special level.

I don’t think there’s anything wrong with paying attention to things that aren’t popular, and in fact spend much of my time doing just that. My taste draws me to a lot of might-have-beens striving to be much bigger pop stars than they are. I think it’s generally good to expand definitions for pop stardom—the “pop” part, anyway. (I don’t care much about the “star” part, except to the extent that I can hear it.) But I do think that if your interest is in either pop music or more broadly “music that is popular,” you probably need to look beyond the local American charts.

Even on the American charts, you still see different sorts of artists showing up at the end of the ‘10s: K-pop and Afrobeats acts, Spanish-language superstars, and hugely successful but hard-to-categorize American post-pop weirdos like Post Malone and Billie Eilish. Rap and country music start to succeed without making big overtures to the pop marketplace. When you expand your horizons to the global charts rather than just the American charts, you see even more stories of global popularity that seem bigger than the many indie-ish post-pop impressionists, nonentity mirages, and outdated impersonators that remain a stubborn focus of American-centric pop conversations.

The pop consolidation and stagnation of the 2010s, and the development of many parallel paths, were the growing pains of the A-pop era. There wasn’t a clean break with the previous era—there was a whole decade of ferment, where sounds and styles and semi-stars worked just outside of the spotlight, in many regions of the world simultaneously, while incumbents hogged the attention. But I think the growing pains are for the most part over. American pop can’t reclaim its past blockbuster authority, but there are still plenty of stars—they’re just further out there.

There were exceptions, and release dates were also a bit more malleable back then, with something sometimes not reaching mass attention until a year or two after it was technically first released. Lots of people I’ve talked to about this also did not experience pop culture the way I did—I may have been more sensitive to these things because I had older sisters who were attempting to cultivate me away from terminal dorkiness.

At a practical level, there are also just too many casual swears in the vast majority of popular songs now, with fewer radio edits. (You can trace the line in Taylor Swift’s gradual incorporation of curse words over a decade—her first “shit” appeared in 2017 and “fuck” appeared in 2020.) Olivia Rodrigo and Sabrina Carpenter don’t get played at school; an accidental glimpse of the cartoonishly gruesome video for “Taste” at a friend’s movie night made my youngest tell me “I think that might have traumatized me” (it was fine). Chappell Roan gets an occasional spin at events for “Pink Pony Club” or “Hot to Go,” both hits with the elementary school’s resident Swifties. When my kids listened to the latest “Weird Al” Yankovic polka medley—which crammed together a full decade’s worth of a pop hits, 2014-2024, and also didn’t sound that old—they were baffled at the sound-effect-heavy section representing “WAP,” a song I couldn’t even begin to describe to them. I defaulted to my usual David Byrne cop out: “I’ll tell you later.”

I think the counterculture development of this music does have a comparable churn—one that I mined myself as a teenager but that my parents were a bit too old to follow until they were much closer to adulthood.

Two major breakout stars of the early ‘10s started out doing formal impersonations: Bruno Mars, who was an Elvis impersonator wunderkind before moving on to Michael Jackson, and Ariana Grande, whose early YouTube presence was filled with canny pop impersonations.

I could go very long on this accounting, but for now, you can just read my thoughts on all this from 2007.

This practice was often overemphasized as a more longstanding norm than it really was in poor pop criticism like John Seabrook’s obsession with the “topliner” role. It’s a little galling for me, a fan of a previous generation of cowriting that was often accused of being part of this “army of songwriters,” to read Seabrook casually refer to someone like Kara DioGuardi as a “topliner.”

The queen of topliners during this period was Sia, who is a fascinating figure in ‘10s pop—someone who I think really excelled as a topliner and especially as a topline singer, but was generally a poor songwriter. I talk about this in some depth with Holly Boson on her podcast Pop Could Never Save Us, about the Sia-soundtracked film Vox Lux from 2018.

Lorde got closer to being a top ten Billboard Artist of the Year than any of her impressionist contemporaries, peaking at #11 in 2014, just like Cyndi Lauper in 1984 (and, for what it’s worth, Chappell Roan in 2024). I am not your go-to guy for Lordeology, so I will refer you to a very good One Week One Band on Lorde from 2014 by Sophia V.

I live near a college, and it has often surprised me what % of songs playing at the parties the students throw on the weekends are the same songs that would have played one or two decades ago. Perhaps it was the same when I was in college and I just never noticed (but I really don't think so!) So I have some bias towards believing the analysis that streaming making the bottom fall out of gatekeeping has fundamentally changed the game.

In any case, wondering if you would consider at some point making a glossary - maybe with a definitive song or two - for each term like 'bort pop' etc?? I started reading your blog sometime during your Taylor Swift series, and I probably read every other post, which means that it can be sometimes disorienting to drop in, and have to do 'remedial' reading to catch up on the terms I missed before

Thank you!

Discovered this *very* A-pop-relevant paragraph on a link supplied by Krugman in one of his enshittification essays (so your most recent post and this one connect!). Of course, "foreign language" may be more of a barrier in TV than in music, but good subtitling (if Americans are willing to stand for subtitles) can at least partially overcome the barrier. My casual reading of the subject says that at the start it was Korean soap operas playing in Japan, Taiwan, and mainland China that fueled Hallyu (the Korean Wave) as much and maybe even earlier than K-pop, and K-pop itself was crossing to Japan seven or eight years before non-Asian-American Americans like me were catching on (BoA hit big in Japan in 2002).

"Another area experiencing growth is international TV formats, much like the trend seen in the music industry. International shows are often cheaper to produce and were not affected by the WGA strike, contributing to an increase in non English SVOD releases from 24% in 2019 to 33% in 2023. In fact, according to Luminate data, 'foreign language' became the most common category for original streaming content in 2023, surpassing all other subgenres for the first time."

--Nick Palmer, "The Rise And Fall Of Peak TV," EssenceMediacom

https://www.essencemediacom.com/thought-leadership/new-communications-economy-entertainment-special-report/the-rise-and-fall-of-peak-tv